Historic photo of early 1900s hospital birth under surgical sterility protocols & general anesthesia of the obstetrical patient

Part 2: Of Blind Alleys and Things that Have Worked: History’s Lessons on Reducing Maternal Mortality word count 4499

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Professionalisation of Delivery Care and Maternal Mortality in Developing Countries

Time series on the evolution of maternal mortality in developing countries are hardier to come by than in the West (Figure 6). There is practically no long term trend information on African countries. There is some more information for Latin America in the second half of the XXth century.

The earliest and most important reductions were obtained where health services are well organised and accessible, countries like Cuba or Costa Rica. For most other Latin American countries the time series are of questionable reliability. They show slower and later reductions, and now stagnate at levels between 100 and 200.

These persistent high levels seem to be related to social inequalities in access to quality health care, compounded by legislation limiting access to safe abortion (Mora & Yunes 1993, Paxman 1993, Rendon et al. 1993).

Historical data in the poorer countries in Asia, such as Laos or Cambodia, are scarce – a notable exception being Sri Lanka. In Sri Lanka registration of births and deaths has been compulsory since 1897 and it has among the best documented time series in developing countries.

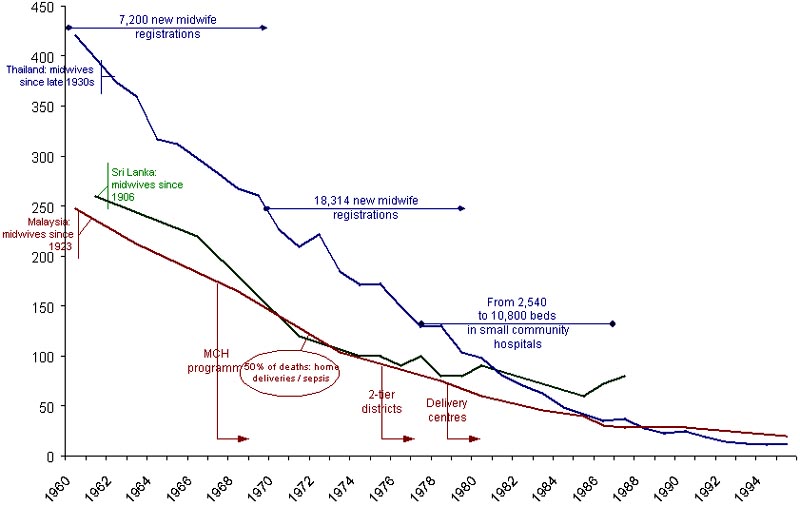

Figure 6. Reduction of maternal mortality after the second World War

What little information there is confirms the importance of information and its utilisation; professional delivery care with accountable and responsive personnel; and a strategy to guarantee access to such professional services. There is negative and positive evidence.

The economic transition in Mongolia, for example, led to the closure of maternities, cut-backs in emergency transport and dwindling hospital supplies. Maternal mortality ratios responded quickly to the breakdown of services, and rose from 120 in 1991 to 210 in 1994 (EA2RS 1996). Likewise, in Iraq the sanctions severely disrupted previously well functioning health care services, and maternal mortality ratios increased from 50 in 1989 to 117 in 1997, and even to 294 in Central and South Iraq (UNICEF 1998).

But there are also examples that confirm that combining a strategy of professionalisation of delivery care with a strong public commitment works (Figure 7). In Sri Lanka maternal mortality levels, compounded by malaria epidemics, had remained well above 1,500 the first half of the XXth century (twenty years of antenatal care notwithstanding). From around 1947 they started to drop, “closely [following] the development of facilities for health care in the country” (Seneviratne & Rajapaksa 2000). The network of facilities was backed up, in 1960, by a special committee appointed to investigate maternal deaths, whilst professional organisations were involved in establishing training and service links. This brought maternal mortality down to between 80 and 100 as of 1975. Malaysia and Thailand are examples of how one can get further down than that.

In Malaysia maternal mortality was in the 120-200 bracket in the 1970s – the equivalent of the US or the UK in the post World-War II years (Leng 1990). In the 1980s ‘low risk delivery centres’ were created, backed up by good quality referral care, all with close and intensive quality assurance and on the initiative of the public sector authorities (Koblinsky et al. 1999). In 1991 Malaysia introduced confidential enquiries (Suleiman et al. 1999). All this brought maternal mortality down to 60-80 in 1990 and further to 20 around 1995.

Figure 7. Maternal mortality since the 1960s in Malaysia, Sri Lanka and Thailand

Up to the 1960s Thailand had maternal mortality levels above 400, the equivalent of the UK around 1900 or the USA in 1939. During the next fifteen years the first three health plans (1961-1976) gave priority to the training of paramedical personnel. During the 1960s 7,191 midwives were newly registered: double the number of the previous decade. Gradually TBAs were substituted by certified village midwives. Mortality halved, down to between 200 and 250 in 1970. During the 1970s the registration of midwives was stepped up: 18,314 new registrations. Midwives became a key figure in many villages: it was the heyday of Thai midwives, as respected figures in the villages, and with a high level of professional and social self-esteem. It also was effective: mortality dropped steadily and caught up with Sri Lanka by 1980, at 98 (Wibulpolprasert 2000). The fourth and fifth health plans then put the main thrust on strengthening and equipping district hospitals. In ten years time, from 1977 to 1987, the number of beds in small community hospitals quadrupled, from 2,540 to 10,800. The number of doctors in these districts rose from a few hundred to 1,339. By 1985 mortality had halved again, down to 42. By 1990 it was down to 25 and in 1995 to 11 per 100,000 – the downside being an impressive medicalisation with 28% of deliveries through caesarean section.

A major commitment of the ministries of public health to organise professional assistance to deliveries clearly works. This, however, is not what happens in many poor countries. Apparently the obstacles they face are not unlike those that delayed reduction of maternal mortality in many Western countries in the first half of the XXth century, including the sometimes appallingly bad quality care in hospitals (Prual et al. 2000).

Inadequate Information

Clearly maternal mortality was not a matter of public concern up to the late 1970s, in spite of the fact that it was broadly at the level which had given rise to major political pressure in Sweden in the XIXthcentury and in Britain in the early XXth. Various factors may have contributed to this.

First, information was hard to come by. Vital statistics in developing countries were – and still are – very much incomplete. In 1977 only 66 countries out of 162 provided (incomplete) data on maternal mortality: in Africa 5 out of 52, in Asia 13 out of 43 and in Latin America 19 out of 31 (Rochat 1981). In those days the only data on maternal mortality in developing countries came from hospitals (Kwast 1988), without the denominator that could give a population perspective. Given the weakness of routine registration, there have been major efforts to provide estimates of maternal mortality through, a.o. the DHS surveys.

This kind of information is, however, much less effective for generating corrective action than, e.g., the confidential enquiries that became routine in the UK at the end of 1950s (Godber 1994). It is even less effective than the data that were available in Sweden in the XIXth century. First, to estimate maternal mortality through surveys is demographers’ work, often performed by foreign experts, with little ownership by authorities, national medical establishment or civil society. This greatly reduces their impact.

Second, maternal mortality ratios only indicate the magnitude of the problem, not its vulnerability. They do not encompass the notion of avoidable deaths that their combination with clinical experience and enquiries in maternal deaths carried in, e.g., the UK.

Third, survey estimates do not provide the degree of disaggregation necessary for planning and priority setting or for mobilising local authorities to respond to their particular situation. To know that 21 women died in a year in one particular district is information of a different kind than to know that MMR is estimated at 530 in the country. The sampling errors are such that even DHS survey estimates cannot be used for more than trend assessment over 10 year-intervals (Stanton et al. 2000).

Second, there is what Graham calls the ‘measurement trap’ (Graham & Campbell 1992) in translating the information into priority setting. Infants under one appear to run a much greater risk of dying than mothers when mortality quotients or rates are measured; for the maternal mortality rates relate to only one pregnancy at a time and not to the total number of pregnancies a mother may have in the course of her life.

As a matter of fact the problem was grossly underestimated. Around 1980 many in academic circles still thought maternal mortality in poor countries was of the order of magnitude of 300/100,000 (Rao 1981, Rosa 1981). Furthermore, donor agencies, planners and a substantial part of the scientific community considered that it was easier to have an impact on the mortality of children than on that of mothers; for child mortality seemed to respond rapidly and visibly responds to a range of vertical programmes (Walsh & Warren 1979). At that time, the 1980s, the international development world was arguing about the correct interpretation of the concept of ‘primary health care’ (Van Lerberghe 1993, Van Lerberghe & De Brouwere 2000). In the meantime things medical, and especially hospitals, were decidedly unfashionable (Van Lerberghe et al. 1997).

If the scientific world and the planners have been slow to appreciate that they were failing to address a huge problem, the same can be said of the health professionals. In developing countries there have been no pressure groups of health professionals comparable to those which were active in Britain and the United States in the early XXth century.

Among specialists in the large hospitals in the capitals, quality of care was not a key feature of the medical culture and it was rare for quality standards to be promoted or monitored. Practitioners in the district hospitals have many priorities, and the lack of resources rapidly leads to fatalism, certainly for problems that are not immediately visible.

Health care providers in the hospitals of developing countries do not expect large numbers of maternal deaths. They are statistically rare (Rosenfield 1989) and doctors are not directly confronted with such occurrences: most of the women who die, do so at home, not in the hospital. The lack of visibility (Ebrahim 1989) is quite convenient in a context where women’s lives are valued poorly, high fertility is culturally rewarded, and health professionals have little in common with their client populations.

The turning point came with the “Where is the M in MCH?” paper of Rosenfield and Maine (Rosenfield & Maine 1985, WHO 1986) and Mahler’s appeal for the Safe Motherhood Initiative in 1987 (Mahler 1987). Ten years later it had become difficult to ignore that a major challenge had to be dealt with. But it was clear, too, that many of the past strategies in poor countries had failed.

Ill-Informed and Ineffective Strategies

Alongside family planning, the first WHO expert committee formally put the focus on antenatal clinics and education of the mothers in the early 1950s (OMS 1952). The package of measures introduced to reduce maternal mortality had long remained substantially the same (in actual fact these measures had mainly been directed towards improving the survival prospects of infants).

Nevertheless, there had been evidence in the industrialised West, for as long as since 1932, that screening for maternal death was not very effective: a letter to the Lancet stated that “80 percent of maternal deaths were due to conditions (sepsis, haemorrhage, shock) not detectable antenatally” (Browne & Aberd 1932, Reynolds 1934). Nonetheless, antenatal risk scoring systems were extrapolated from Europe to developing countries in the 1960s. They soon became common wisdom (Lawson & Stewart 1967, King 1970, Van der Does & Haspels 1972, Cranch 1974) and, during the 1970s and 1980s, mainstream doctrine with WHO’s risk approach (WHO 1978, Backett et al 1984).

In the early-1980s the first evidence questioning the cost-effectiveness of antenatal screening in developing countries appeared (Kasongo Project Team 1984), and common wisdom began to be challenged (Smith & Janowitz 1984): “The ineffectiveness of ANC as an overall screening programme not only renders it less than what it claimed to be; it does not even then say what it is.” (Oakley 1984). Six years later Maine became explicit: “No amount of screening will separate those women who will from those who will not need emergency medical care” (Maine et al. 1991). The Rooney report of 1992 formally changed the balance to scepticism7 (Rooney 1992). It is hard nowadays to defend antenatal care merely on basis of its potential for screening out preventable maternal death – but many are the administrators or funding organisations that continue thinking that as long as antenatal consultations are being conducted, one has done one’s duty. In the meantime a WHO seminar in Malaysia in 1970 had launched the training and promotion of traditional birth attendants as another strategic axis (Mangay-Maglacas 1990). This strategy was further promoted in the influential recommendations of a 1972 inter-country-study. A decade later the initial enthusiasm still persisted (Williams et al. 1985, Tafforeau 1989, Sai & Meesham 1992), but it gradually gave way to scepticism (Chen 1981, Mathews 1983, Belsey 1990, Maine 1991, Bryant 1990, Smith et al. 2000). Little effect was seen apart from tetanus prevention. The resistance (or inability) to change of TBAs, their lack of credibility in the eyes of the health professionals, the de facto impossibility to organise effective and affordable supervision, all have discredited training of TBAs. Whatever its other merits, it is now considered an ineffective strategy to reduce maternal mortality.

Making Professional Care Accessible

It has taken the international community up to the 1990s to realise that the important thing is that deliveries are far safer with professional assistance, and that when a serious problem appears a pregnant woman should have access to an appropriately equipped health service.

Antenatal care or delivery attendance by TBAs without professional obstetric care cannot achieve the same. If the necessity of referral level obstetric care has now become obvious, the need for professional assistance to all deliveries – essential obstetric care – still meets only with limited support, and the medical assistance model clearly is favoured over midwifery. The end result is that some countries have invested all in institutionalisation and medicalisation of childbirth. Others, still put their hopes in antenatal screening and TBAs. Only a minority is investing in the now – at last – WHO-recommended essential obstetric care. EOC is much more credible for and readily accepted by the medical community than the ANC-TBA strategies of the 1970s. Where resources are available EOC expands rapidly and maternal mortality drops. The downside is that it also easily gets translated into institutionalisation and ‘technologisation’ of delivery. In Thailand, for example, the midwifery association has ceased to exist in the early 1990s, and as a rule deliveries now take place in hospitals: 28% through caesarean section.

In countries with severe resource constraints, however, there remain major problems in implementing these strategies. First, because huge investments in time and money are necessary to train the required numbers of professionals: midwives are scarce, 1 per 300,000 inhabitants in a 1990 estimate (Kwast 1991), especially outside the capital cities. Huge investments in time and money are necessary also to provide the necessary referral facilities able to complement a still to be created network of professional assistance to normal deliveries. Resources are not enough, though. Accessibility also has financial, cultural and psychosocial aspects (Jaffré & Prual 1994). Perhaps the most intractable and important issue is that of the accountability of professionals: for the quality of what is done in the hospital, and for what is not done outside (Nasah 1992, Derveeuw et al. 1999).

Winning the Hospital Battle

Historically the concept of avoidable deaths has made it possible for decision makers to realise that the problem is vulnerable. Measuring maternal mortality ratios is not enough. Maternal mortality ratios measurements need to be complemented by information that involves the entire community of maternal care providers, with immediate implications for local action. Various such methods are presently promoted: assessment of Unmet Obstetrical Need (De Brouwere & Van Lerberghe 1998), identification of avoidable deaths through confidential enquiries (Hibbard et al. 1996, Bouvier-Colle et al. 1995, Cook 1989), audits (Filippi et al . 1998), systematic verbal autopsies (Ronsmans 1998, Wessel et al. 1999, Langer 1999). These can contribute to generating information in a format that can be used for pressure through professional organisations and public: pressure for resources and pressure for accountability.

Professionalisation of delivery care is the key. In the Swedish model promotion of delivery care has preceded the impact of hospital technology. One could imagine to try to reproduce a similar sequence: first develop ambulatory midwifery, and later add hospital care. Such an approach would however (i) withhold the benefit to be obtained from the mutual potential of both elements; (ii) lack political credibility, and produce results too slowly; (iii) put the medical establishment in a position of conflict such as in the USA or England & Wales of the first half of the century. Winning the hospital battle (access to quality referral delivery care by accountable professionals) first is crucial from a strategic point of view, and a condition in order to get the doctor’s collaboration in the promotion of professional midwifery (access to quality primary delivery care).

Thinking back on Morocco’s blind spot for maternal health in the 1980s and the reluctance to face the evidence of the dramatic proportions of the problem, one key policy maker observed: “The problem is really too big, you cannot tackle it with a programme, you need to tackle the whole system. That requires such an amount of resources, and above all of efforts.”: investments in training, in health care networks, in transformation of the system to ensure financial accessibility and accountability of the providers. This is unlikely to happen without public initiatives and pressure from the civil society. But the same Moroccan experience shows that progress is possible. It will take time, as it has done in Sweden and in China, in Sri Lanka and in Cuba. If the various elements are put into place, significant and largely irreversible reductions should be possible, even with limited resources. Extrapolating from historical and recent experience, reductions of over 50% in well less than ten years are perfectly realistic. With still nearly 600,000 maternal deaths per year at this moment, it seems worth trying.

References

Backett M, Davies AM and Petros-Barvazian A (1984). L’approche fondée sur la notion de risque et les soins de santé. Notamment la santé maternelle et infantile (y compris la planification familiale). Genève: OMS.

Boerma JT and Mati JK (1989). “Identifying Maternal Mortality through Networking: Results from Coastal Kenya.” Stud.Fam.Plann. 20(5),245-253.

Borst CG (1988). The training and practice of midwives: a Wisconsin study. Bull. Hist. Med. 62:606-627.

Bouvier Colle MH, Varnoux N, Bréart G and Medical Expert Committee (1995). “Maternal deaths and substandard care: the results of a confidential survey in France.” Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 58, 3-7.

Browne FJ and Aberd (1932). “Antenatal care and maternal mortality.” Lancet (July 2),1-4.

Cook R (1989). “The role of confidential enquiries in the reduction of maternal mortality and alternatives to this approach.” Int.J.Gynecol.Obstet. 30, 41-45.

Cranch GS (1974). “The role of nursing/midwifery in maternal and infant care.” In: Nursing-midwifery aspects of maternal and child health and family planning, Washington: PAHO, p.30-34.

De Brouwere V & Van Lerberghe W (1998). Les besoins obstétricaux non couverts. Paris: L’Harmattan.

De Brouwere V, Tonglet R & Van Lerberghe W (1997). “La ‘Maternité sans Risque’ dans les pays en développement: les leçons de l’histoire” Studies in Health Services Organisation & Policy, 6, Antwerp, ITGPress.

Declercq E and Lacroix R (1985). The immigrant midwives of Lawrence: the conflict between law and culture in early twentieth-century Massachusetts. Bull. Hist. Med. 59,232-246.

Derveeuw M, Litt V, De Brouwere V & Van Lerberghe W (1999). “Too little, too late, too sloppy: delivery care in Africa”. Lancet 353, 409.

Donnison J (1988). Midwives and Medical Men: A History of the Struggle for the Control of Childbirth. Hienemann, London.

Duncan JM (1870). On the mortality of Children and Maternity Hospitals. Edinburgh, Adam and Charles Black.

EA2RS (1996). Mongolia: poverty assessment in a tranistion economy. World Bank.

Ebrahim GJ (1989). “Safe Motherhood in the 1990s”. J Trop Pediatr 935(6),272-273.

Filippi VG, Alihonou E, Mukantaganda S, Graham WJ and Ronsmans C (1998). “Near misses: maternal morbidity and mortality.” Lancet 351,145-146.

Fox DM (1993). “The medical institutions and the state” In Companion encyclopedia of the history of medicine, vol. 2 W. F. Bynum & R. Porter, eds., Routledge, London & New York, pp. 1204-1230.

Fraser GJ (1998). African American Midwifery in the South. Dialogues of birth, race, and memory. Harvard University Press, Cambridge Mass & London.

Godber G (1994). The origin and inception of the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 101,946-947.

Graham WJ & Campbell OMR (1992). “Maternal health and the measurement trap.” Soc. Sci. & Med. 35,967-977.

Graham WJ, Brass W and Snow RW (1989). “Estimating maternal mortality: the sisterhood method.” Stud.Fam.Plann. 20 (3),25-135.

Hibbard BM, Anderson MM, Drife JO, Tighe JR, Gordon G, Willatts S et al. (1996). Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom 1991-93, London: HMSO.

Högberg U, Wall S and Broström G (1986). “The impact of early medical technology of maternal mortality in late XIXth century Sweden.” Int.J.Gynecol.Obstet. 24, 251-261.

Jaffré Y & Prual A (1994). Midwives in Niger: an uncomfortable position between social behaviour and health care constraints. Soc. Sci. Med. 38(8),1069-1073.

Jahn A, Razum O & Berle P (1998). Routine screening for intrauterine growth retardation in Germany: low sensitivity and questionable benefit for diagnosed cases. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 77,643-648.

Jahn A (1999). Is the risk approach in antenatal care still justified? Lessons from Tanzania and Germany. Gynaecology Forum, 4(4),14-18.

Kasongo Project Team, Van Lerberghe W & Van Balen H (1984). “Antenatal screening for fetopelvic dystocias; a cost- effectiveness approach to the choice of simple indicators for use by auxiliary personnel”, J Trop. Med Hyg. 87,173-183.

King CR (1991). “The New-York maternal mortality study: a conflict of professionalization.” Bull. Hist. Med. 65 (3),476-502.

King M (1970). Medical care in developing countries: a symposium from Makerere, Nairobi: Oxford University Press, 309 pages.

Koblinsky MA, Campbell O & Heichelheim J (1999). Organizing delivery care: what works for safe motherhood? Bull. World Health Organ 77(5),399-406.

Kwast BE (1988). Unsafe motherhood: a monumental challenge. A study of maternal mortality in Addis Ababa, Leiderdorp, The Netherlands.

Langer A, Hernandez B, Garcia-Barrios C, Saldaña-Uranga GL and National Safe Motherhood Committee of Mexico (1999). “Identifying interventions to prevent maternal mortality in Mexico: a verbal autopsy study.” In: M. Berer and Sundari (eds) Safe Motherhood Initiatives: critical issues, 127-136.

Lawson B and Stewart DB (1967). Obstetrics and Gynaecology in the Tropics and Developing Countries, London: Edward Arnold.

Leng HC (1990). Health and Health Care in Malaysia. Institute for Advanced Studies Monograph Series SM 3. University Malaya.

Llewellyn-Jones D (1974). Human Reproduction and Society. London: Faber and Faber.

Loudon I (1992a). Death in childbirth. An international study of maternal care and maternal mortality 1800-1950 Oxford University Press, London.

Loudon I (1992b). “The transformation of maternal mortality.” BMJ 305,1557-1560.

Loudon I (1997). “Midwives and the quality of maternal care.” in: Marland H and Rafferty AM, Midwives, Society and Childbirth. Debates and controversies in the modern period. Routledge, London & New York, 180-200.

Mahler H (1987). “The Safe Motherhood Initiative: a call to action.” Lancet, 668-670.

Maine D, Rosenfield A, McCarthy J, Kamara A and Lucas AO (1991). Safe Motherhood Programs: options and issues, New-York: Columbia University.

Mangay-Maglacas A (1990). “Traditional birth attendants.” In: Health care for women and children in developing countries, edited by H. M. Wallace and K. Giri, Oakland (USA):Third Party Publishing Company, p. 229-241.

Marland H (1997). “The midwife as health missionary: the reform of Dutch childbirth practices in the early twentieth century”, In Marland H & A. M. Rafferty, eds.: Midwives, Society and Childbirth. Debates and controversies in the modern period., Routledge, London, pp. 153-179.

Marland H and Rafferty AM (1997). Midwives, Society and Childbirth. Debates and controversies in the modern period. Routledge, London & New York.

Maternal and Child Health Division Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan and Mothers’ and children’s Health and Welfare Association (1992). Maternal and Child Health in Japan, Tokyo: Mothers’ and Children’s Health and Welfare Association.

Mora G & Yunes J (1993). Maternal mortality: an overlooked tragedy. In: Gender, women, and health in the Americas, pp. 62-79, ed E. Gómez Gómez, Washington: Pan American Health Organization.

Mottram J (1997). “State Control in Local Context. Public health and midwifery regulation in Manchester, 1900-1914.” in: Marland H and Rafferty AM, Midwives, Society and Childbirth. Debates and controversies in the modern period. Routledge, London & New York, 134-152.

Oakley A (1984). The capture womb. A history of the medical care of pregnant women. Basil Blackwell, Oxford.

OMS (1952). Comité d’experts de la maternité. Premier rapport. Etude préliminaire. SRT n°51, Organisation Mondiale de la Santé, Geneva, 28p.

Paxman JM, Rizo A, Brown L & Benson J (1993). The clandestine epidemic: the practice of unsafe abortion in Latin America. Stud. Fam. Plann. 24(4),205-226.

Pearl R (1921). “Biometric data on infant mortality in the United States Birth Registration Area, 1915-1918.” Am.J.Hyg. 1,419-439.

Porges RF (1985). “The response of the New-York Obstetrical Society to the report by the New-York Academy of Medicine on maternal mortality, 1933-34.” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 152,642-649.

Prual A, Bouvier-Colle MH, de Bernis L & Breart G (2000). “Severe maternal morbidity from direct obstetric causes in West Africa: incidence and case fatality rates”, Bull. World Health Organ 78(5),593-602.

Rao KB (1981). “Maternity care.” In: Maternal and child health around the world, edited by H. M. Wallace and G. J. Ebrahim, London: The Macmillan Press Ltd, p. 76-81.

Reagan LJ (1995). Linking midwives and abortion in the progressive era. Bull. Hist. Med. 69,569-598.

Rendon L, Langer A & Hernandez B (1993). Women’s living conditions and maternal mortality in Latin America. Bulletin of PAHO 27(1),56-64.

Reynolds FN (1934). “Maternal mortality” Lancet (29 December):1474-1476.

Rochat RW (1981). “Maternal mortality in the United States of America”. Wld. Hlth. Statist. Quart. 34,2-13.

Ronsmans C, Vanneste A-M, Chakraborty J and van Ginneken JK (1998). “A comparison of three verbal autopsy methods to ascertain levels and causes of maternal deaths in Matlab”, Bangladesh. Int. J. Epidemiol. 27,660-666.

Rooney C (1992). Antenatal care and maternal health: how effective is it? A review of evidence, Geneva: World Health Organization.

Rosa FW (1981.) “The status of maternal and child care in developing countries.” In: Maternal and child health around the world, edited by H. M. Wallace and G. J. Ebrahim, London: The Macmillan Press Ltd, p. 3-16.

Rosenfield A & Maine D (1985). “Maternal mortality: a neglected tragedy. Where is the M in MCH?” Lancet 2 (446),83-85.

Rosenfield A (1989). “Maternal mortality in developing countries: an ongoing but neglected ‘epidemic’.” J.A.M.A. 262,376-379.

Schmidt WM & Valadian I (1969). “Maternal and child health activities.” In JJ Hanlon ed Principles of Public Health administration, The CV Mosby Company, Saint Louis, 367-381.

Seneviratne HR & Rajapaksa LC (2000). “Safe motherhood in Sri Lanka: a 100-year march”, Int.J.Gynaecol.Obstet. 70(1),113-124.

Smith JB, Coleman NA, Fortney JA, De-Graft Johnson J, Blumhagen DW & Grey. TW (2000). The impact of traditional birth attendant training on delivery complications in Ghana. Health Policy & Planning15(3),326-331.

Smith JS & Janowitz B (1984). “La surveillance prénatale.” In: Janowitz B, J Lewis, N Burton and P Lamptey Santé reproductive en Afrique Subsaharienne: les questions et les choix, USA: Family Health International, 19-22.

Stanton C, Hill K, AbouZahr C & Wardlaw T (1995). Modelling maternal mortality in the developing world. WHO & UNICEF, Geneva.

Stanton C, Abderrahim N & Hill K (2000). “An assessment of DHS maternal mortality indicators”. Stud.Fam.Plann. 31(2),111-123.

Strong TH Jr (2000). Expecting Trouble: The Myth of Prenatal Care in America, New York: New York University Press.

Suleiman AB, Mathews A, Jegasothy R, Ali R & Kandiah N (1999). “A strategy for reducing maternal mortality”, Bull.World Health Organ 77(2),190-193.

UNICEF (1998). Situation analysis of children and women in Iraq. Unicef, New York.

Van der Does CD and Haspels AA (1972). “Antenatal care.” In: C. D. Van der Does and A. A. Harpels, ed. Obstetrical and gynaecological hints for the tropical doctor, Utrecht: A. Oosthoek’s, 1-6.

Van Lerberghe W, de Béthune X & De Brouwere V (1997). “Hospitals in sub-Saharan Africa: why we need more of what does not work as it should?” Trop Med Int. Health 2(8),799-808.

Van Lerberghe W & De Brouwere V (2000). “Etat de santé et santé de l’Etat en Afrique subsaharienne”, Afrique Contemporaine 135: 175-190.

Van Lerberghe W (1993). “Les politiques de santé africaines: continuités et ruptures”, Bull Séances Acad R Sci Outre Mer. 39, 205-230.

Wessel H, Reitmaier P, Dupret A, Rocha E, Cnattingius S & Bergstrom S (1999). “Deaths among women of reproductive age in Cape Verde: causes and avoidability”, Acta Obstet.Gynecol.Scand. 78(3),225-232.

Walsh JA & Warren K (1979). “Selective Primary Health Care: an Interim Strategy for Disease Control in Developing Countries”, N.Engl.J.Med., 301:967-974.

WHO (1986). “Maternal mortality: helping women off the road to death.” WHO Chronicle 40(5),175-183.

WHO and UNICEF (1996). Revised 1990 estimates of maternal mortality. A new approach by WHO and UNICEF, Geneva: WHO.

Wibulpolprasert S ed. (2000). Thailand health profile 1997-1998. Ministry of Public Health. Bangkok, ETO Press.

World Bank (1995). World Development Report 1995. Workers in an integrating world. Oxford University Press, New-York.